THE QUAKERS IN CHICHESTER 1655 - 1967

Michael Woolley

4th edition

Published by the Religious Society of Friends, Chichester Meeting

Copyright Michael Woolley 2006

First published 1998

Second edition 1999

Third edition 2000

Fourth edition 2006

Fourth edition reprint 2014

Copyright Michael Woolley 1998, 1999, 2000, 2006

------------

1: Seekers and Radicals

On a Saturday in the late summer of 1655 a strange little group made its way from Arundel into Chichester. They almost certainly approached the town down the street called St Pancras which led to one of the city's still standing gates. Most of the buildings both in the street and in Eastgate Square had been flattened in the Civil War thirteen years earlier, and apart from a little row of newly built cottages adjoining the site of St Pancras church, there would have been a clear view of the city walls.

Second edition 1999

Third edition 2000

Fourth edition 2006

Fourth edition reprint 2014

Copyright Michael Woolley 1998, 1999, 2000, 2006

------------

1: Seekers and Radicals

On a Saturday in the late summer of 1655 a strange little group made its way from Arundel into Chichester. They almost certainly approached the town down the street called St Pancras which led to one of the city's still standing gates. Most of the buildings both in the street and in Eastgate Square had been flattened in the Civil War thirteen years earlier, and apart from a little row of newly built cottages adjoining the site of St Pancras church, there would have been a clear view of the city walls.

George Fox

George Fox

There were at least two travellers, quite possibly more. The leader was a 31 year old roaming preacher called George Fox, an eccentric and difficult man. His way of dressing may well have attracted attention as the group entered the town as it was very distinctive: for many years he was given to wearing a leather suit and an extremely large hat. His hair was unfashionably long and, though he avoided any hint of Royalist colour or finery, even the Puritans (the Royalists' greatest enemies) thought his appearance rather odd.

Fox was no figure of fun though: he had great presence, and some would suggest that despite his strange appearance he was very attractive, his strong personality giving him a dangerous magnetism. Several of the people who met him wrote of his amazing eyes. In a superstitious age there were those who associated his penetrating gaze with witchcraft, a capital crime at the time, though not one of which he was ever formally accused.

It is unlikely that he had been an easy travelling companion on the road from Arundel, as he was given to impenetrable silences interspersed with passionate and sometimes lengthy outbursts. But it must also be said that he inspired tremendous loyalty - the other known traveller, for instance, as he entered Chichester that day, was Ambrose Rigge, a young man of twenty or twenty one who had left home just to follow him. Fox was an inspirational character, sometimes drawing crowds of hundreds to hear him preach.

His message was outspoken and uncompromising and as a result he was familiar with the inside of various prisons. Yet the last time he had been inside one, in the spring of that same year, he had been sent to meet Cromwell himself, and had, moreover, been given his liberty by the Lord Protector. In short he was a powerful and highly complex person who, despite his humble origins, and his remarkable ability to annoy people, was a national character.

It is unlikely that he had been an easy travelling companion on the road from Arundel, as he was given to impenetrable silences interspersed with passionate and sometimes lengthy outbursts. But it must also be said that he inspired tremendous loyalty - the other known traveller, for instance, as he entered Chichester that day, was Ambrose Rigge, a young man of twenty or twenty one who had left home just to follow him. Fox was an inspirational character, sometimes drawing crowds of hundreds to hear him preach.

His message was outspoken and uncompromising and as a result he was familiar with the inside of various prisons. Yet the last time he had been inside one, in the spring of that same year, he had been sent to meet Cromwell himself, and had, moreover, been given his liberty by the Lord Protector. In short he was a powerful and highly complex person who, despite his humble origins, and his remarkable ability to annoy people, was a national character.

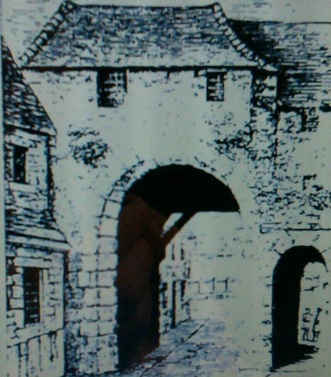

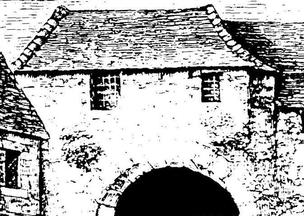

The East Gate of Chichester by Grimm 1782

The East Gate of Chichester by Grimm 1782

Passing through the East Gate the travellers would have found themselves in East Street, but a rather different looking street from that of today as the great building boom of the early eighteenth century had not yet given Chichester its characteristic Georgian appearance. The houses and shops were still timber framed and many had top floors which jutted out over the roadway in the Tudor fashion. At number 21, on the corner of St Andrew's Court, they would have passed the house of William Cawley, the local MP, the man who had captured the town for Parliament, assembling his forces on the Broyle fields just to the north of where the Festival Theatre stands today. Cawley is chiefly remembered as one of those who sat in the High Court which condemned Charles I. Indeed he was one of those who signed the death warrant. Later, after the monarchy had been restored, loyal Cicestrians erected a bust of the unfortunate Charles in the market cross, on the east side, looking sternly down the road at the house in which his tormentor had lived.

Fox was 'religious' and Cawley 'political' but were both products of the Reformation, an extraordinary period of ecclesiastical and cultural revolution which had been going on for the previous hundred and twenty years. Henry VIII had made the initial break with Rome, instituted some overdue reforms (of church finance for example) but had otherwise been something of a reconciler, trying to keep the country united and his 'high church' and 'low church' citizens all within a single Church of England. Edward VI, who followed him, was much more decisively Protestant, and his commissioners ruthlessly stripped churches of their and the nation's artistic heritage. Crucifixes were pulled down, statues defaced and paintings destroyed. Chichester Cathedral still bears the marks of their depredations.

After King Edward came Queen Mary and under her the country reverted to Catholicism, land previously taken from the 'high' bishops was restored to them, and Cranmer was burnt at the stake in Oxford. Even here in Chichester there were two unfortunates burnt in the cathedral precincts, Thomas Iveson and Richard Hook. Little is known of Hook but Iveson was a carpenter arrested with two others for reading the Bible in English. Urged to recant, he refused to do so and was martyred on 24th July 1555, just a hundred years before the visit of Fox.

Elizabeth, who took the throne in 1558, was like her father Henry, monarch for around forty years, and like him she wanted her church to be all things to almost all men. This was a policy she pursued with such skill that while the English church turned 'low' again, and the 'high' bishops lost their estates again, and the country filled up with returning Protestant exiles, she was not finally excommunicated by the Pope until twelve years after her accession.

These great shifts and swings in ecclesiastical policy were to continue. The Catholics made an attempt on the life of King James in 1605, the Gunpowder Plot, while his son King Charles was so ill thought of by the Puritans that when the country was riven by civil war, in 1642, one of the primary aims of Parliament was to make the country safe for Protestantism.

Elizabeth, who took the throne in 1558, was like her father Henry, monarch for around forty years, and like him she wanted her church to be all things to almost all men. This was a policy she pursued with such skill that while the English church turned 'low' again, and the 'high' bishops lost their estates again, and the country filled up with returning Protestant exiles, she was not finally excommunicated by the Pope until twelve years after her accession.

These great shifts and swings in ecclesiastical policy were to continue. The Catholics made an attempt on the life of King James in 1605, the Gunpowder Plot, while his son King Charles was so ill thought of by the Puritans that when the country was riven by civil war, in 1642, one of the primary aims of Parliament was to make the country safe for Protestantism.

It was from this ferment that Quaker beliefs and Fox, their greatest early exponent, were to spring. The same thoughts were occurring to different people in different parts of the country. In 1646, Oliver Cromwell, not yet more than a soldier, had voiced an interesting idea, "To be a Seeker is the next best sect to a Finder, and such shall every faithful humble Seeker be at the end". In Nottinghamshire, and independently of Cromwell, a group of open-minded searchers for truth, the Children of Light, emerged in 1648. In Westmorland, and also independently of Cromwell, another similar movement was known as the Westmorland Seekers. For over a hundred years different groups of Christians had been proclaiming so many, sometimes irreconcilable, truths, that seeking, in humble and faithful fashion, was an appealing notion to many people. It was an idea whose time had come, and in Fox the various seekers found a voice and a leader. This was the man who came into Chichester that Saturday afternoon in 1655.

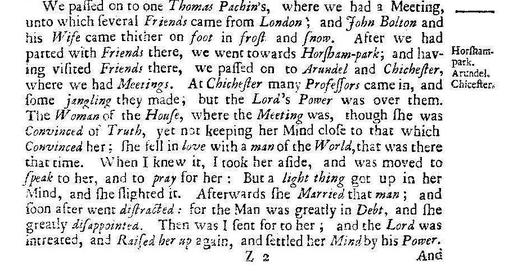

Extract from an original copy of George Fox's Journal.

Extract from an original copy of George Fox's Journal.

That night he and his people stayed at a woman's house, probably that of Margery Wilkinson who lived on the site of what is today 62/3 North Street. A meeting was held in the house and Fox was to write later in his Journal that "... many professors came in and some janglings there were, but the Lord's power was over all" which is to say there were a lot of believers, some disturbance, but that it was a worthwhile and reverent meeting. He goes on to recount how the woman of the house was "convinced", but was in love with a man, also present at the meeting, whom she later married, and then discovered to be a bad lot. She was, in the Journal's words "greatly distracted", but later returned to Quaker ways, meeting Fox on at least two further occasions, both before and after she was widowed.

The reason for thinking this woman might have been Margery Wilkinson is that she, Margery, was later prominent in the Chichester Meeting, indeed the Sunday meetings for worship were held in her house in 1669. She was also a widow by that time. It is not specifically recorded that Fox ever visited Chichester again, but he did travel in Sussex in 1657, visiting friends, and also in 1668, so they may have met each other again on those occasions.

The reason for thinking this woman might have been Margery Wilkinson is that she, Margery, was later prominent in the Chichester Meeting, indeed the Sunday meetings for worship were held in her house in 1669. She was also a widow by that time. It is not specifically recorded that Fox ever visited Chichester again, but he did travel in Sussex in 1657, visiting friends, and also in 1668, so they may have met each other again on those occasions.

The Guildhall

where Fox may have met the Mayor

The Guildhall

where Fox may have met the Mayor

The account in the Journal is supplemented by that of Ambrose Rigge who records that the next morning, Sunday, Fox went to the Baptist meeting, at that time held in a house in South Street. He was "listened to for a while but at length taken by the constable before the Mayor." This strongly suggests that he spoke without invitation, interrupting the service (something he was very prone to do) until the embarrassed Baptists had him hauled away.

The story gets more revealing, for the Mayor, one Richard Manning, fell in a rage with him for not taking off his hat, a normal courtesy in the seventeenth century. Fox refused to take off his hat to anyone, and frequently got into trouble as a result. He insisted that all men should be treated with equal respect as all "had that of God in them". He also insisted on always using the familiar second person singular, 'thee/thou', rather than the more respectful 'you', for the same egalitarian reasons. The revolution which had led to the King's execution had opened men's eyes to the possibility of a less hierarchical world.

The egalitarianism of Fox reflected the ideas of the period: the Levellers, for example, were adherents of a popular democratic movement which insisted that authority should only be wielded with the consent of the people - an elected Parliament should be sovereign, its power only qualified by a respect for basic human rights. The equality of men was another idea whose time had come during the Civil War and it was an idea which greatly influenced George Fox and his followers.

The story gets more revealing, for the Mayor, one Richard Manning, fell in a rage with him for not taking off his hat, a normal courtesy in the seventeenth century. Fox refused to take off his hat to anyone, and frequently got into trouble as a result. He insisted that all men should be treated with equal respect as all "had that of God in them". He also insisted on always using the familiar second person singular, 'thee/thou', rather than the more respectful 'you', for the same egalitarian reasons. The revolution which had led to the King's execution had opened men's eyes to the possibility of a less hierarchical world.

The egalitarianism of Fox reflected the ideas of the period: the Levellers, for example, were adherents of a popular democratic movement which insisted that authority should only be wielded with the consent of the people - an elected Parliament should be sovereign, its power only qualified by a respect for basic human rights. The equality of men was another idea whose time had come during the Civil War and it was an idea which greatly influenced George Fox and his followers.

His refusal to doff his cap to the Mayor of Chichester, or anyone else, was widely copied by other Quakers: there is a story told of the high-born William Penn who, many years later, on being received for an audience with Charles II, was surprised to see the King remove his own headgear. "Why dost thou take off thy hat, Friend Charles?" he is supposed to have asked. "It is the custom of this place that only one man should go hatted at a time" replied the King urbanely.

It seems the Mayor of Chichester was not quite so urbane in his dealings with Fox though he did let him go, apparently unconvinced by the accusation that the man was a Jesuit. This accusation was not uncommon at the time, there being much paranoia about disguised Catholics fomenting revolution. The situation was not helped by Quaker refusal to swear the Oath of Allegiance which had been introduced after the gunpowder plot, supposedly to ensure that all Catholics were loyal citizens. The problem for Quakers was that they refused to swear any oaths (and still do incidentally), on the basis of New Testament teaching - let your yea be yea, and your nay be nay. It must be assumed that the Oath was not tendered at Fox's appearance in the Chichester Court for he would most certainly have declined it and been imprisoned. As it was he was allowed to go, having been searched, and two days later left for the West of England.

It seems the Mayor of Chichester was not quite so urbane in his dealings with Fox though he did let him go, apparently unconvinced by the accusation that the man was a Jesuit. This accusation was not uncommon at the time, there being much paranoia about disguised Catholics fomenting revolution. The situation was not helped by Quaker refusal to swear the Oath of Allegiance which had been introduced after the gunpowder plot, supposedly to ensure that all Catholics were loyal citizens. The problem for Quakers was that they refused to swear any oaths (and still do incidentally), on the basis of New Testament teaching - let your yea be yea, and your nay be nay. It must be assumed that the Oath was not tendered at Fox's appearance in the Chichester Court for he would most certainly have declined it and been imprisoned. As it was he was allowed to go, having been searched, and two days later left for the West of England.

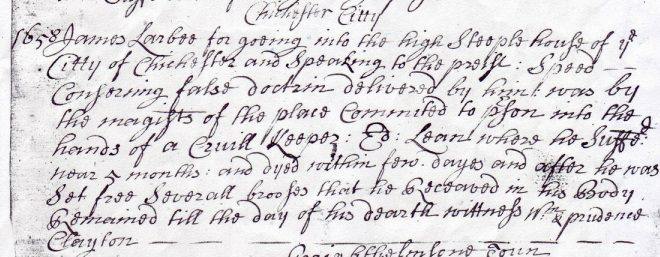

The Larboo story in the 1670 Book of Sufferings

The Larboo story in the 1670 Book of Sufferings

So began the Quaker, or Friends' Meeting in the town. (The official name is The Religious Society of Friends, but the word Quaker is much used and was even incorporated into early Acts of Parliament). Records of the meeting are sparse in those early years but some do exist. In 1658 an early member, James Larbel, went into the high steeplehouse (the Cathedral) took issue with the priest for preaching false doctrine, and was arraigned before the magistrate. He was sent to prison and suffered for five months at the hands of the gaoler Edward Lean. He died a few days after his release still bearing several bruises from the beatings he had received. Joanne, his wife, died the following year and was buried with him in Whyke churchyard on the corner of Quarry Lane and Whyke Road.

There were other burials, a sad case of a different kind being that of Jeane Smith, John Smith's daughter, in 1661, followed shortly after by her mother Grace. They were buried in St Andrews, now the Centre of Arts but then the parish church of William Cawley. John Smith was a prominent member seven years later in 1668 - the Meeting was being held in his house in the Hornet (somewhere between the Eastgate and Bush Inns). He married his second wife, Priscilla, in the same year.

Earlier, in 1663, Timothy Hale had written his will, appointing his body to be buried at the discretion of Friends in his "herb garden at Easthampnett, at the east end thereof" where his grave would catch the afternoon sun. He left bequests to named members and five pounds for "those that labour in the Word" (travelling preachers like Fox) and another five pounds for "poor Friends belonging to the Meeting".

In 1664 William Clayton of Whyke (who had testified to Larbel's suffering) was imprisoned for six months for attending a Quaker meeting. William's name comes up a lot in those early years: it was he who in 1670 testified to Larboo's story. The first recorded mention we have of his name is in 1659 when, with Richard Green, he was a witness at the Quaker marriage of Thomas Cowdry and Sarah Dobbin.

Friends became very careful to record marriages in order to avoid any accusation of impropriety in relationships which were not strictly legal. Records are sparse until 1668 when an organisational structure was established, but there were clearly Quakers in Chichester from 1655 - albeit without all the minutes and records which later became such a feature of Quaker life.

Earlier, in 1663, Timothy Hale had written his will, appointing his body to be buried at the discretion of Friends in his "herb garden at Easthampnett, at the east end thereof" where his grave would catch the afternoon sun. He left bequests to named members and five pounds for "those that labour in the Word" (travelling preachers like Fox) and another five pounds for "poor Friends belonging to the Meeting".

In 1664 William Clayton of Whyke (who had testified to Larbel's suffering) was imprisoned for six months for attending a Quaker meeting. William's name comes up a lot in those early years: it was he who in 1670 testified to Larboo's story. The first recorded mention we have of his name is in 1659 when, with Richard Green, he was a witness at the Quaker marriage of Thomas Cowdry and Sarah Dobbin.

Friends became very careful to record marriages in order to avoid any accusation of impropriety in relationships which were not strictly legal. Records are sparse until 1668 when an organisational structure was established, but there were clearly Quakers in Chichester from 1655 - albeit without all the minutes and records which later became such a feature of Quaker life.

Charles glaring down the street

Charles glaring down the street

2: Suspected of Sedition 1660:1700

During the ten years following George Fox's first visit there were dramatic changes in government which were to have a profound effects on all Quakers. Cromwell died in 1658 and after two years of uncertainty Charles II was invited to return from exile and assume the crown. Charles had smoothed the way to his return by issuing the Declaration of Breda promising a general amnesty, respect for Parliament and religious toleration. The amnesty, known as the Act of Oblivion, was duly passed, the only exceptions being people involved in the execution of his father. William Cawley was exiled to the Continent, never returned to Chichester, and never saw the bust of Charles I glaring down the street at his front door.

During the ten years following George Fox's first visit there were dramatic changes in government which were to have a profound effects on all Quakers. Cromwell died in 1658 and after two years of uncertainty Charles II was invited to return from exile and assume the crown. Charles had smoothed the way to his return by issuing the Declaration of Breda promising a general amnesty, respect for Parliament and religious toleration. The amnesty, known as the Act of Oblivion, was duly passed, the only exceptions being people involved in the execution of his father. William Cawley was exiled to the Continent, never returned to Chichester, and never saw the bust of Charles I glaring down the street at his front door.

Charles II kept his promises to Parliament but Parliament itself, now filled with distrustful Royalists, made religious toleration impossible. The Quakers were seen as radical Puritans and quite possibly seditious. The country seethed with plots and rumours of plots. It was only twelve years since the horrors of the Civil War and the execution of the last King, so men who refused to take oaths, wouldn't pay tithes, insisted on wearing their hats, and spoke to their betters in the familiar thee/thou form were promptly singled out for retribution. No matter that one of their number, Margaret Fell, presented to King and Parliament the Peace Testimony which was to become a classic part of Friends' tradition. "We are a people that follow after those things that make for peace, love and unity...(We) do deny and bear our testimony against all strife and wars and contentions". Parliament was unconvinced: the Friends had too much in common with the Levellers – men who had actively fomented mutiny.

Cells where felons were held above the gate

Cells where felons were held above the gate

The Quaker Act of 1662 was one of the series of measures curtailing religious liberty known collectively as the Clarendon Code. It became illegal to refuse an oath, and illegal for five or more Quakers to assemble for worship. The Meeting in Arundel was raided and the members brought to Chichester to be sentenced. They were hobbled together in chains and paraded down the main streets to the gaol above the East Gate where they were treated very brutally by the gaoler. Gaolers at the time made their living by charging the prisoners for their keep - the Arundel men were asked a groat a night - and Friends who wouldn't pay (as a form of protest) were harshly treated. Two of their number, Nicholas Rickman and Edward Hamper, were separated from the rest and "thrown in with the felons" rather than being kept in the relevant comfort of the jail keeper's house.

Another of the early victims of the legislation against holding meetings was the young William Penn (later the founder of Pennsylvania) who was sent down from Oxford for attending a Quaker meeting. The response of Chichester Friends to the oppression is not known but elsewhere in the country valiant stands were taken and Quakers continued to meet in public despite the widespread attacks and imprisonments. They refused either to conceal their meetings or to respond to taunts other than by turning the cheek. This combination of straightforwardness and non-aggression in the face of persecution won them considerable sympathy and within months the King had ordered the release of all but the ringleaders. In 1668 much of the legislation expired and was not replaced for another two years, and then with less repressive measures.

It was in that year that an organisational structure was decided upon for the emerging sect. Local Meetings were grouped together geographically and met once a month in administrative sessions called, very logically, Monthly Meetings. Chichester was part of the Chichester and Arundel Monthly Meeting which also included Steyning (just north of Worthing), Petworth, and Birdham. The latter was a short lived assembly of some twenty or thirty people which met in the house of one Richard Green who with his wife got into trouble with the authorities for wilfully absenting himself from his parish church, a legal offence.

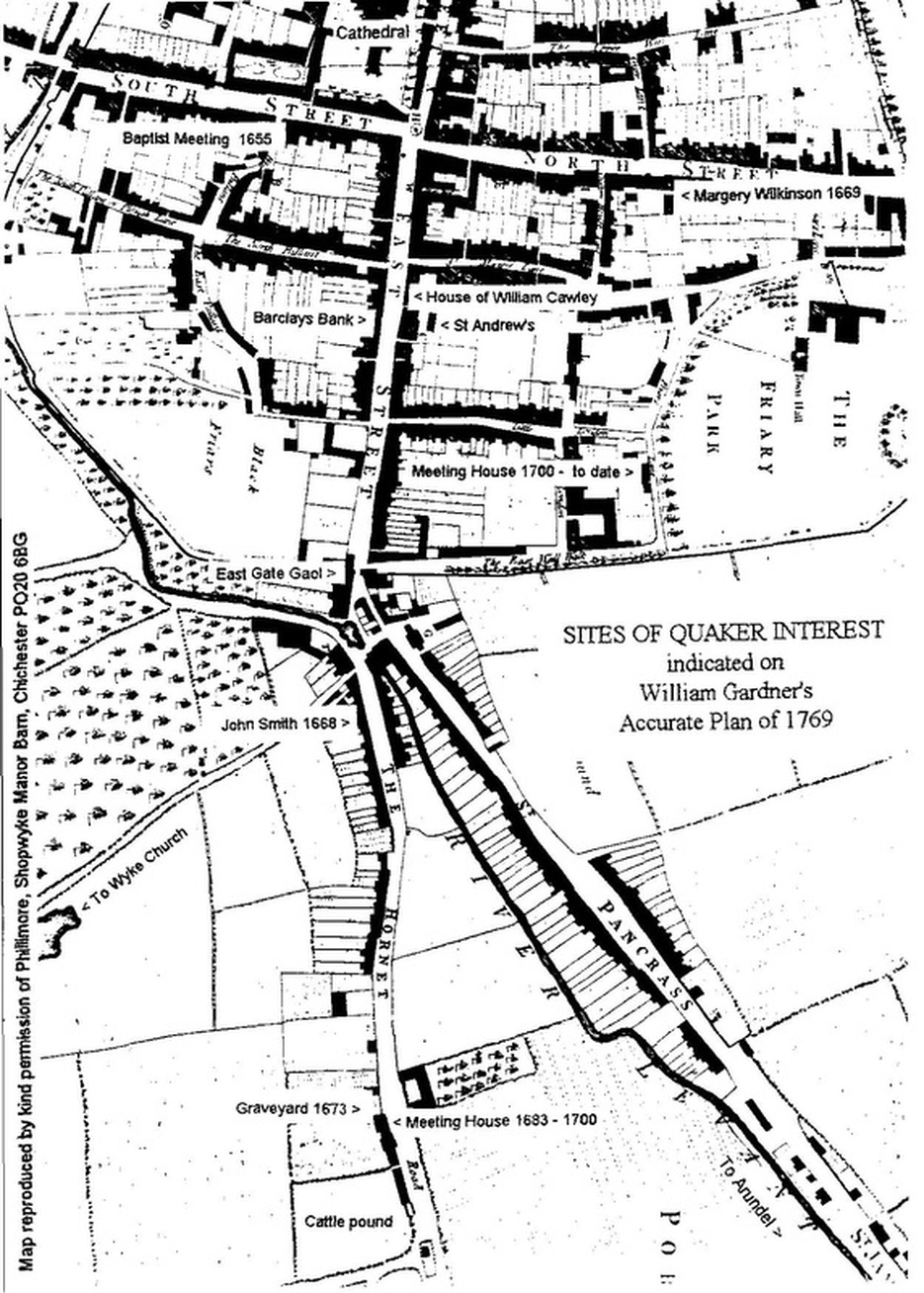

Red indicates where Meetings were in the early C18, blue where they are today.

Red indicates where Meetings were in the early C18, blue where they are today.

On the sixth of October the first Monthly Meeting was held in Arundel, and it was not a happy day for Chichester. It is minuted that arrangements were put in hand for two respected Friends from other parts of the county to visit the Cathedral City and "exhort all those who have dishonoured God in the Meeting". There is no indication as to exactly what form the dishonour had taken. The reproof would have been delivered "in the high red house of John Smith in St Pancras," the parish not the street, for John Smith lived in the Hornet. The minute, incidentally, is dated 6th Day of the 8th Month. This Quaker form of dating was an eccentricity at the time, avoiding any reference to heathen gods long before the rest of the world started using all figure dates. Before the reform of the English calendar the year began in March so the eighth month was October. Friends also numbered weekdays from one to seven, the First Day being Sunday.

First Day meetings in 1669 were being held at Margery Wilkinson's house in North Street where, on the 6th July, Chichester's third Quaker marriage took place between Joshua Kirck of Leadenhall in London and Margaret Reynolds. Nothing more is heard of this couple who presumably went to live at Joshua's house in London. Margery Wilkinson though appears in the records again three years later when, together with Richard Green, Edward Hamper and others, she leased a piece of land in the Hornet for use as a burial ground. It was a thousand year lease and the burial ground is still there, now a Quaker freehold, and let to the District Council as a small garden.

Edward Hamper was one of those who had been thrown in with the felons in the East Gate gaol. He was a man of property and after this experience he created, in 1675, an unusual legal trust to protect his estate from seizure. His Arundel houses were made over to Quaker trustees in return for a modest annual income. There were many trustees, each of whom could act alone, so that if the Meeting were raided there was a reasonable chance that someone would still be available to manage the estate. This precaution was not of immediate use, as life became a little easier for Dissenters during the 1670s. Laws were amended and a Declaration of Indulgence made by the King. There were still some problems though, as in 1678 when William Cooper of Whyke was accused by the church wardens of having Quaker meetings in his house.

Peter Gunning (Clare College Cambridge)

Peter Gunning (Clare College Cambridge)

Sussex Quarterly Meeting requested Ambrose Galloway, a draper from Lewes, to collect information from Friends about their sufferings. He recorded them year by year starting back in 1655 listing fines and imprisonments. Some Chichester members had suffered imprisonment in those early years, and in addition to this legal persecution there was an unusual extra-legal challenge in Bishop Peter Gunning, who was appointed to the see in 1670. This man was so ardent that he is reported to have disturbed dissenting meetings in person, but he does not seem to have been vicious. Indeed, unusually for the age, he gave a public challenge to Quakers, Presbyterians and Baptists and appointed three days for disputation in the Cathedral.

Disputation of another kind took place in the courts, in London, where William Penn was charged with attending the Gracechurch Street Meeting. The jury refused to find him guilty despite being dreadfully bullied by the judge who twice sent them away, without food or other comforts, to reconsider their verdict. After three days of this the judge imprisoned them all, for contempt of court. A considerable legal struggle ensued but finally the point was won and the rights of an English jury established.

A few years later Penn inherited considerable property in Sussex and came to make his home at Warminghurst near Pulborough. It is probable that he visited Chichester, the county town and only twenty miles away, though there is no actual record of his having done so. The Chichester Meeting would certainly have had regular contact with Warminghurst, which was to be an important Quaker centre for the thirty one years that it was home to Penn. In 1677, for example, after the London Yearly Meeting, he entertained the Quaker leaders George Fox and Robert Barclay. The authorities came to hear that illegal religious meetings were being held in the house and those present expected to be raided by the militia. In an act of open defiance a huge open air meeting was arranged, several hundred Friends attended, probably including some from Chichester. There was great tension but in the event they were undisturbed.

Young Penn in pre Quaker armour!

Young Penn in pre Quaker armour!

William Penn was not only an effective leader but also a prolific writer. Pepys, was surprised by his book on the Trinity. "I got my wife to read it to me and I find it so well writ as I think it too good for him ever to have writ it - and it is a serious sort of book and not fit for everybody to read." One of the first guests at Warminghurst was another thinker and writer, Robert Barclay whose 'Apology' is a Quaker classic, asserting that no man could be regarded as excluded from salvation: a doctrine of inclusivity. The idea was very different from that of the Presbyterians, for example, who at the time were fiercely pre-destinationist, believing that only the elect could find grace. The Puritans had devised tests to make their churches companies of people each of whom was destined for 'salvation'. The Quakers avoided both tests and sacraments: no humble faithful seeker was excluded. Much was borrowed from Puritan Christianity, plain meeting houses and transparent honesty for example. But much was different - the unprogrammed meetings, where anyone could speak if so moved, (as is still the case today) and, most importantly, that there was no prescription for salvation, just companionship on the road thereto.

Duke of Monmouth hat-off

Duke of Monmouth hat-off

By 1679 the road must have seemed relatively comfortable in Chichester, widespread persecution had abated and Quakers were receiving de facto acceptance. When the Duke of Monmouth (a popular focus of opposition) visited the City in the February of that year, he was visited by a Quaker tobacco pipe maker who was introduced as a very honest man. He was graciously received, the Duke with his hat off and the Quaker with his hat on. “How many attend your meetings?” asked the great man. “About a hundred and we are all for thee.” The Duke then asked if they were disturbed as they met but “No” said the Quaker “we are not molested".

They were however still the object of official suspicion – the above story is from an alarmed letter written by Bishop Carleton to his Archbishop. A hundred was a relatively large group as Chichester’s population was less than three thousand at the time. It must have been difficult to accommodate a hundred in a private house and shortly after the Friends rented themselves a building for worship. It was on the far side of the burial ground in the Hornet, right on the edge of the town, adjoining the field used as a cattle pound.

Then in 1683 came the Rye House Plot and the road suddenly became much more difficult. Some prominent Whigs were uncovered in a plot to assassinate the King, and in the hiatus which followed the Tories were in the ascendant, and determined to control any potential trouble-makers. A great new wave of religious persecution swept the country. In Chichester this was to reach a climax in July and then to continue unabated till October. The suffering was graphically recorded at the time: "...Friends belonging to Chichester Meeting being met together at their usual meeting place at or near Chichester, the soldiers then quartered at Chichester came in amongst them and violently broke the glass windows of the house and the tables forms and benches all to pieces and were so rude and abusive to the women Friends that they could no more than keep themselves from their beastly designs on them ... but it pleased the Lord in wonderful manner to preserve them without the mischief on their persons" Frustrated in their attacks on the women the soldiers dragged the whole assembly out of the place by force.

The Meeting had been denounced by informers, and because of the information laid by them warrants for distress were granted against attenders. These warrants were an early form of fine, paid in goods rather than cash. A poor smith, the Richard Green from Birdham who had previously been in trouble for not attending his parish church and who now attended the Chichester Meeting, lost two hogs, his bed, bedding, vice, sledges and iron, in all worth four pounds ten shillings. The informers returned repeatedly, often drunk, and accompanied by soldiers. The following account has all the marks of being dictated by a group of people all chiming in excitedly with their own points and memories. The clerk who recorded it was so harassed that he failed to include any full stops.

"They were constant abusers of the innocent, they several times broke the windows of the house and the doors, and the door of the burying ground, and laid the burying ground open to the highway and burned the fence which was about it, and as often as Friends made any small reparations of anything they came and destroyed all, the following meeting, and stuffed up the meeting house doorplace, having before carried away the door, with bushes and thrust the bushes against Friends' legs, and tore a Friend's scarf from her neck and bid Friends complain to the justices if they would, and if any small matter for seats was provided by laying a few bricks and loose boards on them, they came and broke all to pieces, and threw a serpent, as they call it, composed of powder etc (a kind of firework) into the meeting which was like to have done mischief, being a thatched house, and affrighted the children at the meeting, and all this performed with great swearing and threatening and chiefly enacted by the two informers who were commonly drunk when in this service, and sometimes accompanied with the rabble of rude boys and others, the informers telling Friends that if they would be obedient to the King's laws and come to church etc all would be well."

It was too much for Margery Wilkinson who went off and complained first to the Bishop's Chancellor, (a senior legal officer) and then to the magistrates. She got short shrift from them. They told her that Friends were meeting illegally and nothing could be done. The attendant constable gave an old fashioned warning about the law taking its full course if any more were heard. It seems that she ignored the warning and did complain again for shortly after her name appears in the list of those imprisoned in Horsham Gaol. She was soon released – but in the case of Henry Dixon events took a terrible course: he too was sent to prison by the Chichester court and he died there three months later. The oppression was not to last much longer though: in 1685 King Charles died, James II came to the throne, and the political atmosphere changed for the better.

Admiral Penn by Peter Lely

Admiral Penn by Peter Lely

In 1681, two or three years before these events, Charles II had settled a long-standing debt to the Penn family by licensing the American territory then known as West Jersey to William. The King wanted the new colony renamed in honour of William's father, Admiral Penn, and given the wooded countryside there, the title Pennsylvania was decided upon. In 1682 William left Warminghurst for the New World with about a hundred Friends, many from Sussex, mainly from the Horsham Monthly Meeting but some perhaps from Chichester. He was one of only a very few colonial proprietors of his day to visit America.

Philadelphia on the Delaware river. Chichester to the south west.

Philadelphia on the Delaware river. Chichester to the south west.

There were already a few Quaker settlers in the new colony when Penn and his group arrived. William Clayton and his family from Chichester had moved there in 1677. Clayton was the carpenter from the suburb of Whyke who had witnessed the suffering of James Larbol in 1658 and been imprisoned himself in 1664. The family undoubtedly knew Penn from their days in Sussex where Clayton had been treasurer of the Monthly Meeting and active in Quarterly Meeting affairs. In 1682 he sold Penn 206 acres of what is now central Philadelphia, and in 1683 he was elected to the Council where he took an active part on the committee that revised the ‘Frame of Government’ (the constitution) of the colony. About the same time the family, with other Friends, established a township a few miles to the west of Philadelphia and called it, nostalgically, Chichester. Early meetings for worship were held in members' homes.

The liberal constitution which Penn, Clayton and the Friends wrote for the Quaker state was in many ways ahead of its time. Peaceable relations were established with the Native American communities, there was religious freedom for all, the death penalty all but abolished. Oaths and military spending were both excluded from law and government. Slavery was not abolished but slaves were guaranteed their freedom after a certain period of service. A few years later Penn was to suggest another idea ahead of its time - a union of the American colonies. When this was finally achieved a hundred years later, and independence gained, the constitution of the new United States was much influenced by that of Pennsylvania.

Penn himself did not stay long in the colony he had so helped to establish but returned to his family in Sussex two years later, landing at Worthing in 1684. Perhaps it was Penn who carried back the cheerful letter from William Clayton dated 1683: "We have no cause to mourn. Our lot is fallen every day in a goodly place, and the love of God is growing among us, and .... truly great is our joy therefor."

In England the times were not so happy. Edward Hamper died in Horsham gaol in 1684 having been arrested again the previous year, at the time when Chichester Friends suffered so much. Hamper was a shoemaker in Arundel and comfortably off: in addition to his Trust, which became a Quaker Charity on his death, he left money to many members of his family and also his old friend Ambrose Rigge, the man who had travelled to Chichester with George Fox thirty years before. Among his family was included his cousin John Martin, a member of the Chichester Meeting.

Hamper seems to have had close ties with Chichester for he also left money to some members to whom he was not related including both Richard Green and Margery Wilkinson, who each received twenty shillings. A further five pounds was left to Margery and John Hammond jointly "to be of their disposing about their meeting house", a useful bequest after the damage caused by the soldiers, informers and 'rude boys'. Shortly after, perhaps because of the problems which Friends' occupation of the building had provoked, the landlord decided to sell it. The 1687 freehold was in three names, John Martin, John Hammond and the trustees of the Quarterly Meeting. This complicated arrangement was to cause problems later.

One problem of which Friends were to be relieved was that of persecution, for with the accession of William and Mary there came the Toleration Act which ended most of the penalties for religious dissent (though it left the Clarendon laws on the statute book). This reform was passed just in time for George Fox and Robert Barclay to see it: Barclay died in 1690, Fox in 1691, the first generation of Friends was ending. The death of Fox was marked by a letter from the London Yearly Meeting testifying, as is the Quaker custom, to "the grace of God as shown in his life." One of the signatories was Ambrose Rigge, the then young man who had accompanied Fox when he first came to Chichester in 1655. Margery Wilkinson fades from the record in the 1680s but as her death is nowhere recorded she perhaps wet to spend her old age away from the town.

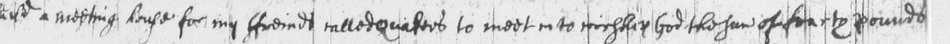

Will of James Lucas 1693 "...build a meeting house for my friends called Quakers to meet in and worship God the sum of forty pounds".

Will of James Lucas 1693 "...build a meeting house for my friends called Quakers to meet in and worship God the sum of forty pounds".

A death which was recorded was that of James Lucas in December 1693. He was a very prosperous carpenter who earlier the same year had leased a site in Eastgate which had stood empty since the Civil War. Then he was taken ill and by November was so sick that he made his will, providing generously for his five young children, his loving wife Ann and his mother Joanne. He also left the impressive sum of forty pounds to "build a meeting house for his friends called Quakers to meet in to worship God". In those days such a sum was sufficient to buy a small building - it was largely because of the generosity of Lucas that Friends were eventually able to move to the Priory Road site.

William Penn, who was living in Warminghurst at the time, would certainly have heard about this dramatic development in Chichester. He was virtually under house arrest in 1693 for though repression was slowly easing it was not yet entirely over. He occupied himself writing a short treatise entitled "An essay towards the present and future peace of Europe by the establishment of a European Parliament". The next year Penn was completely acquitted of all the charges against him, and there was further sign of relaxing attitudes when, in 1696, an Act was passed which allowed Quakers to affirm instead of taking the oath. This Act was a mixed blessing, for while on the one hand it relieved Friends, on the other it marginalised them, not allowing them to give evidence in criminal cases, to serve on juries or bear any office or place in government. The radical, confrontational movement of the 1650s and 60s was being domesticated and isolated, and this is reflected in the reaction of Chichester Meeting to the Lucas bequest. The young George Fox might well have found some dynamic way to use the money - to establish a new meeting in a place where there was none perhaps - but by the 1690s, after years of difficulties, fines and imprisonments local Friends were not so adventurous and settled on a new building for the existing Meeting.

Matters did not move fast. It was five years later in 1698 that the Monthly Meeting discussed the possession and repair of the Hornet building, which had been purchased only ten years before. It was reported to be in a very dilapidated state, partly perhaps because of the attacks in '83, (when Friends were only renting it) though it must also be remembered that at this period most buildings were constructed of timber, with little or no foundation, and it was typical for such structures to need constant repair and renewal.

In August 1698 Monthly Meeting decided to sell. However there was a difficulty, for by this time John Martin, who had a share in the freehold, had also died. His heir was the thirteen year old Josiah whose articles of apprenticeship had been paid by Quarterly Meeting at considerable expense eight months earlier. When it was discovered that he was also receiving an income from Friends in the form of interest on his share in the Meeting House there were second thoughts. It was felt that he should pay some of his apprenticeship himself and negotiations were started with his grandfather, Nicholas Rickman, acting as his guardian.

The matter was resolved by December when Quarterly Meeting finally approved the sale, but the following March (1699) it was reported that, though some progress had been made with both the sale and the finding of a new site, neither matter "was yet perfected". This was perhaps a good thing for the money from the Lucas will had still not been received. In June 1699 it was reported that there was prospect of payment. It was not in fact until December that John Hammond and James Steel were able to inform the meeting that they had at last obtained it.

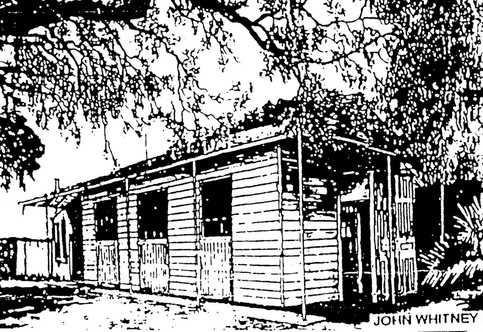

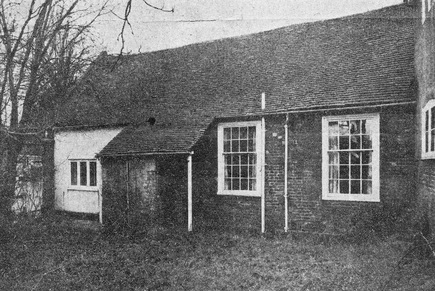

1700 Meeting House in 1967

1700 Meeting House in 1967

By April 1700 a site had been found, a piece of ground which may have previously housed a cockpit. It was in Priory Street (sic) and surrounded on three sides by the land of Cockpit House, today known as Friars' Gate. It was a quiet corner: the street ended then at the city walls which were still complete at this point (a breach was made and the street extended in the nineteenth century). Opposite sheep were grazed in the big field belonging to the Duke of Richmond. Monthly Meeting met on 2nd April and members present, including Richard Green the Birdham blacksmith, gave consent to Hammond and Steel to "bargen and by (this) peace of ground in order to build a meeting house in Chichester." In June it is reported that the old meeting house had been sold (for fifty four pounds) and finally, by 7th November 1700, that the new one was completed.

Interior of 1700 Meeting House

Interior of 1700 Meeting House

It was a plain wainscoted room with two large sash windows and a raised bench for the elders. After the attacks seventeen years before the building was designed for security with no ground floor windows onto the street, though there were two on the first floor which could serve as look-outs if necessary. The yard was protected by a high wall and a stout door through which any marauder would have to pass before passing a second door into the meeting room. Happily these precautions were never needed: the years of violence had ended and the new building knew only tranquillity.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Meeting in Chichester Pennsylvania was also prospering and the first, timber built, meeting house was erected in 1703, just three years after that in Priory Road.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Meeting in Chichester Pennsylvania was also prospering and the first, timber built, meeting house was erected in 1703, just three years after that in Priory Road.

3: Sobriety and Good Works 1700:1908

The year 1700 was a turning point for Friends in many different ways. The generational change was marked again when Richard Green, one of the very early members, died in 1702. William Penn was also growing old – he left Warminghurst in 1707 and retired to Buckinghamshire.

|

Quaker Minute 6th day of 5th month 1702:

Whereas James Steel of Chichester of ye county of Sussex, house carpenter, the bearer hereof, having formally acquainted us of his intending to transport himself and wife and family into Pennsylvania in America, and also requesting of a certificate and we, after deliberate enquiry, finding nothing to obstruct his said intentions, do leave him to his liberty and freedom and do hereby certify whom it may concern that the said James has behaved himself in life and conversation to the best of our knowledge very honest and just, and according to his ability, have been very servicable amongst us so parting in true unity and fellowship desiring his prosperity and welfare we salute you all in Truth. |

Penn had returned to Sussex in 1701 after his second trip to Pennsylvania. It is very probable that he visited his county town, Chichester, and saw the new meeting house there. Perhaps he met James Steel, who had found the site, and spoke to him of the new colony: at all events it was in 1701 that James and his wife Martha and their two small children decided they would like to emigrate. There was opposition from James’s mother and until she gave consent the Meeting would not give its backing. Consent came the next year and on 6th August the Meeting wrote a generous letter of introduction, an important matter guaranteeing the young family welcome and support in the new colony.

|

Like the Claytons before them the Steels prospered in America: in due course James became Receiver General of Land and in 1715 a Member of the State Assembly and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. America’s gain was, of course, England’s loss – Chichester Meeting was changed by the departure of one of its most active and committed young families and meetings throughout Britain were undergoing the same experience.

Another change was in the social composition of the group. In the early years Friends were drawn from a wide spectrum of society including people like Penn, whose father was an admiral and a courtier. However the repression which started with Clarendon had its effect: men of substance did not give up their faith but their sons and heirs did not usually follow them. With the restoration of the monarchy times were different, believers were often imprisoned and heavily fined. For wealthy young men with a lot to lose it was a daunting prospect. On the other hand the aspiring poor did continue to join: they had less to lose in terms of personal wealth and more to gain in terms of mutual support. By 1700 the social composition of the group had become much more humble but from then on honesty, hard work and the aforesaid mutual support helped members to better themselves and move up the social scale.

Humility and aspiration make men law-abiding. There were no fresh challenges to convention like those of the early radicals, which had so often led to dire punishment. Quakers still affirmed, used the thee/thou and refused to doff their hats, but these things had become tolerated as religious eccentricities. As early as 1683, when two London Friends went to plead the Quaker case with the King, they reported that a courtier "gently removed our hats". As if to emphasise their new role as harmless misfits, Friends adopted a sort of uniform (Quaker dress) in the early years of the new century. It was as unthreatening a testimony as the monk's habit.

Another change at this point was the emergence of social work programmes: Bristol Meeting started a job creation scheme and school in 1696, London started a similar programme in 1702, though it was the school that prospered and lives on today as the Friends' School at Saffron Walden. Chichester was not so ambitious but did help a steady stream of individuals, sometimes very substantially as in the case of Ann Roberts who was paid an allowance sufficient to live on, or Josiah Martin, the orphan boy apprenticed in 1698.

Another individual helped was John Palmer who lived for several years rent free in the room above the meeting house. In 1737 there was some irritation that he had taken a house closer to town yet had not cleared his goods. He was given notice to clear his room and deliver the key by Michaelmas or pay fifty shillings a year rent. He was still there twelve months later, claiming that a well was needed, which wasn't deemed reasonable. He finally left the following year.

One of the reasons for the length of this dispute may have been Quaker decision making. Then as now meetings had to be called, and the "sense of the meeting" had to be discerned, a simple majority was not enough. This was a matter of principle - what was important was to gain the truth not a majority in a vote. This remains an unusual idea in Western societies where virtually all decision making, in the courts or Parliament for example, is adversarial. The Quaker way is not and this can be time consuming.

John Palmer was not the only person to leave: membership was falling throughout the country, a tendency which Friends shared with Baptists, Presbyterians and Independents during the whole of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A major cause of decline for Quakers at this time was the dismissal of members who married out. Under external pressures they had become much less open minded than in the early years. Excluded from mainstream society they supported each other in very real and practical ways, providing the sort of benefits today given by the State, but in return the Meeting felt entitled to exercise great control over members' lives. The case of James Grace in Chichester is typical. He was married by a priest to a woman not a Friend. Members appointed by the Meeting, visited him and expressed their concern but did not feel he was taking the matter seriously enough. He was formally disowned by the Society in December 1769, but there were expressions of sorrow and hope of his repentance. Others suffered the same fate for marrying out while at least one did not marry at all - Sarah Chandler, a servant, was disowned for committing fornication. Affairs of the heart were not responsible for all dismissals - a man called Dalby was read out of the Meeting for the 'disgraceful treatment' of his brother, but exactly what he had done is not recorded. Sometimes matters were settled less drastically - Inigo Chipper for example made a written confession in the minute book and expressed his sorrow. He had got disgracefully drunk "as is my nature" and then picked a fight. He stayed a member.

Stern discipline and legal discrimination both combined to reduce membership. As early as 1737 the Petworth, Steyning and Birdham Meetings of the Chichester Monthly Meeting had closed, and the decline continued throughout the century. In 1822 the Chichester and Lewes Monthly Meetings amalgamated but had only three congregations between them: Chichester, Brighton and Lewes.

Perhaps one of the reasons for Chichester's continuance was its ownership of the meeting house. Moreover a trust deed had been drawn up in 1768 stipulating that it and the graveyards be used as such for ever. There could never thereafter be any question of selling them and putting the proceeds to different purpose. It was at almost exactly this time that Thomas Walls, the owner of the adjoining house (Friars' Gate), did some very extensive remodelling, giving it a Georgian facade. It is possible the trust deed was drawn up as the result of a bid to purchase the meeting house and enlarge the Friars' Gate garden.

At this time there was a challenge of a different kind for American Friends: the timber built meeting house in Chichester Pennsylvania burnt down but was quickly replaced by the stone building which still stands and is now on the US National Register of Historic Places. The great-great grandparents of President Abraham Lincoln were members and there are probably several of his ancestors in the graveyard.

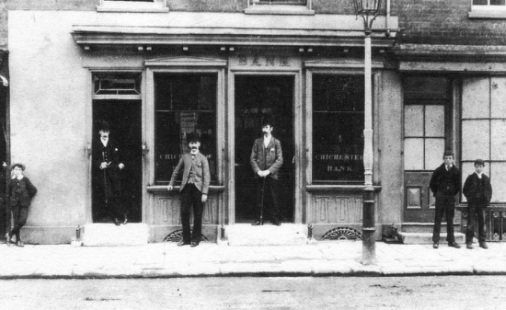

The Chichester Bank in the late 19th century

The Chichester Bank in the late 19th century

In Britain while the eighteenth century was not a good period for the movement as a whole it was a time when many individual Friends enjoyed personal success. Inoculation against smallpox was developed by three Quakers; Coalbrookdale (a cradle of the industrial revolution) and the world's first iron bridge were built by Friends; Joseph Fry, a Bristol apothecary, founded the chocolate company. The Lloyd brothers could not go to Oxford like their father as the universities barred Dissenters, so they went into business and eventually founded the bank which bears their name. Barclays was started by descendants of Robert Barclay, while in Chichester James Hack and Charles Dendy founded the Chichester Bank in 1809 - it operated from premises in East Street and prospered throughout the nineteenth century, eventually being incorporated with Barclays as a going concern. The present 1961 building has a plaque in the porch commemorating the Hack Dendy partnership.

30 Little London. The curriers was the white building

30 Little London. The curriers was the white building

Banking was not the only prosperous Quaker business in Chichester. James Hack’s brother Stephen inherited the curriers (leather merchants) founded by his father, and in 1804 moved it into the extensive Little London premises recently occupied by the City Museum on the corner of East Row. Stephen lived for a time in the adjoining house (no. 30) which became a great centre of Quaker activity throughout the nineteenth century.

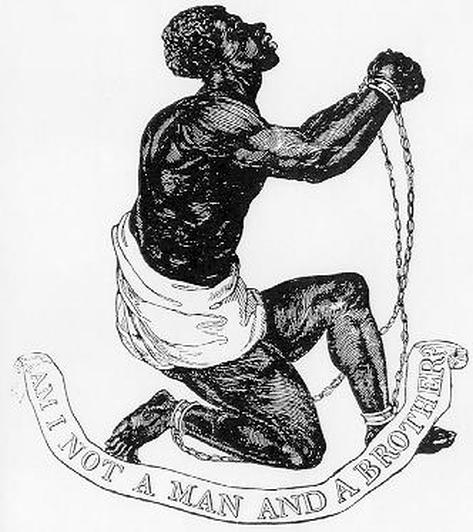

Friends' concern for social problems continued and developed. In 1772 slavery became an issue when John Woolman spoke at the Yearly Meeting greatly raising awareness. When the first National Anti-Slavery Committee was formed nine of the twelve members were Quakers. Three petitions organized by Friends were sent to Parliament in the following years, and the first anti-slavery Bill was passed in 1807 with strong support from the Society, though Quakers were still excluded from Parliament and had to rely on the MP William Wilberforce, not a Friend, to promote it.

Friends' concern for social problems continued and developed. In 1772 slavery became an issue when John Woolman spoke at the Yearly Meeting greatly raising awareness. When the first National Anti-Slavery Committee was formed nine of the twelve members were Quakers. Three petitions organized by Friends were sent to Parliament in the following years, and the first anti-slavery Bill was passed in 1807 with strong support from the Society, though Quakers were still excluded from Parliament and had to rely on the MP William Wilberforce, not a Friend, to promote it.

Elizabeth Fry

Elizabeth Fry

Elizabeth Fry began her prison reform work in Newgate a few years later, establishing a school there, in 1817, for the children of the inmates. She was an inveterate campaigner and had visited Chichester in 1815 and 1816. On the first occasion she stayed with John Barton and his wife, and on the second with the Hacks. She was “poorly” the whole time but there were, never-the-less, two “well attended and very satisfactory public meetings”.

The Newgate school was in a tradition of Quaker education. In 1779 a new school was started at Ackworth, in Yorkshire, for boarding children "whose parents are not in affluence". Chichester Monthly Meeting was asked to support the venture with a subscription in 1805. In America the Meeting in Chichester Pennsylvania founded a grammar school in 1793. A most significant educational venture in Britain was the foundation by the Quaker Joseph Lancaster, in 1801, of Borough Road, a free London day school. It attracted great attention, George III subscribed, and its success led to the foundation of The British and Foreign School Society, a formative influence in the development of state education.

Assembly Room

Assembly Room

Joseph Lancaster visited Chichester on 13th September 1810 at the invitation of the local Quaker John Barton and his friend, the diarist and composer John Marsh. Marsh was in his late fifties, not a Friend but much respected, Barton barely 21 but formidably talented and dynamic – probably the instigator of the invitation. Marsh took the chair at the meeting in the Assembly Rooms and Lancaster spoke about his monitorial system, which basically consisted of a teacher drilling older pupils who then drilled younger ones, allowing one adult to instruct very large numbers of children. Following his visit committees were formed, subscription lists opened and by 1812 two schools were established. John Barton was deeply involved and sat on both the boys' and the girls' committees, only resigning in 1850, two years before his death. His brother in law, Stephen Hack of the Chichester Bank family, also served and other Quakers feature in the subscription lists. The schools were non-sectarian, and though Friends took a leading role in their establishment and management, the vast majority of the pupils were from the C of E. When the state system finally absorbed the two secondary schools they were allowed to keep the name Lancastrian until late in the twentieth century. The name still lives on at the Lancastrian Infants’ School.

John Barton was an economist of some repute – interestingly he met Malthus on a visit to Paris in 1816. Ricardo, Malthus and John Stuart Mill all refer to his thesis on the Influence of Machinery on Labour. Karl Marx refers to Barton in Das Kapital, and the London School of Economics has some of Barton manuscripts to this day.

Literary and Philosophical Society

Literary and Philosophical Society

He was well known in Chichester both as a businessman and a man of letters. The Lancastrian Schools were not his only interest in education. In 1825 he was one of the original promoters of the Mechanics’ Institute and “for many years he lectured within its walls in an able and popular manner”. He remained treasurer of the Institute until it merged with the Literary and Philosophical Society and the new joint institution moved into the splendid new building it had constructed, and which still stands at 45 South Street.

The reputation of Quakers at the beginning of the nineteenth century was quite different from that of the early days. They were no longer seen as surly and possibly dangerous radicals, but rather as a sober and disciplined people given to good works and worthy of respect. In 1814, for example, the then Tsar, Alexander I, made a progress along the south coast of England and almost certainly passed through Chichester. At Portsmouth he had expressed the wish to visit a family of Quakers and a house had been suggested. There was such a crowd when he arrived that the plan was abandoned. However a few miles further on he saw a family in their Quaker dress standing at their gate. The coach was stopped and the royal party descended, “most courteously introduced themselves and went in to take refreshment”. They asked about the Meeting, were friendly with the children and after a short stay bade an affectionate farewell. The family were called Rickman and may have been descendants of the Nicholas Rickman so badly treated by the Chichester gaoler in 1662, grandfather to Josiah Martin the orphan boy apprenticed 1698.

The growing esteem in which Friends were held led to new self confidence in public life. By 1820 John Barton felt able to vigorously (verbally) attack the Chichester MP, William Huskisson, at an election meeting in the Assembly Rooms. He received great applause – somewhat to the alarm of his uncle, the banker James Hack, who perhaps feared reprisals.

His other uncle, Stephen Hack the currier, died in 1823, his funeral being attended by much of Chichester society, including John Marsh the composer, who gives a detailed account of the Quaker Meeting for Worship in his diaries.

In the same year Friends again took a prominent and controversial part in the public life of Chichester when they took the leading part in a committee campaigning to abolish slavery itself (not simply the slave trade) throughout the British Empire. The first meeting was held in the home of James Hack and other Quakers, including John Barton, attended. Barton’s father (not a Chichester man) had been one of the nine Friends on the original anti-slave trade committee. The local campaign lasted over two years culminating in January 1826 when, after a final meeting in Hack’s house, there was a great public meeting in the Assembly Rooms. The Duke of Richmond was in the chair, both Chichester MPs attended and the Chichester Petition was duly signed by many of the most important and influential people in the City, including the Dean and the Archdeacon. The Duke then presented it to the Lords and the two MPs to the Commons. It was some years till an Act was passed abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire but Chichester, and Chichester Friends, had played their part.

A few years after the Chichester Petition the esteem in which Friends were held nationally was reflected in the law. The Test and Corporation Acts were finally repealed in 1828. Quakers at last enjoyed full civil liberty.

About this time the Hacks made enquiries of the Quakers in Yorkshire asking about a young man, Thomas Smith, whom they wanted to take on as a business partner. The ability of Friends to contact reliable people in all parts of the country was an important element in their business successes. In buccaneering times the network of trustworthy men and women who belonged to the Society, and who could always be called upon as fellow Friends, was a valuable asset.

Smith must have received the endorsement of the Yorkshire Quakers for he duly became a partner. A few years later, when Barton Hack, Stephen Hack’s son, was advised by his doctor to seek a better climate, it was to the Smiths that he sold the business. He then sailed with his family for South Australia, just established as a Crown Colony, and at the time spoken of by Friends as the “Pennsylvania of the South”.

Adelaide Friends' Meeting House

Adelaide Friends' Meeting House

The family arrived in 1837 and Hack rapidly became an influential figure in the establishment of the new town of Adelaide. He was the first government contractor, a friend of Gawler the second Governor, served on numerous committees and named some of the streets, among them Barton terrace honouring his uncle and Sussex Street his home county. Pennington (sic) Terrace, probably named after the Quaker theologian Isaac Penington, was the site of the 1840 meeting house. The land was given by Hack but the building by the London Yearly Meeting which shipped it out, prefabricated, from England. It is still in use, the oldest place of worship in Adelaide and now on the official Australian heritage list. Today it is entirely surrounded by the buildings of the Anglican Cathedral so as Friends sit quietly on Sunday mornings they can hear the sound of their neighbours’ hymn-singing.

Barton Hack

Barton Hack

Barton Hack's early success is reminiscent of that of William Clayton and James Steel in Pennsylvania a hundred and fifty years earlier. Quaker emigrants tended to do well, they were responsible and hard working. They were also, from Quaker business meetings, in which all members take part, very familiar with the process of making group decisions: it is not surprising that all these men became involved in government.

There is a sad end however to the Quaker connection with Barton Hack - a great collapse in property values in the 1840s made him bankrupt and owing large sums to at least one other member of the Meeting. He left the Society of Friends at this time, perhaps in shame and finding it easier to make a new start in fresh company. Friends appear to have dealt kindly with him, he himself offered no explanation for the resignation. The family became Methodists.

There is a sad end however to the Quaker connection with Barton Hack - a great collapse in property values in the 1840s made him bankrupt and owing large sums to at least one other member of the Meeting. He left the Society of Friends at this time, perhaps in shame and finding it easier to make a new start in fresh company. Friends appear to have dealt kindly with him, he himself offered no explanation for the resignation. The family became Methodists.

Graylingwell Farmhouse as Anna Sewell knew it.

Graylingwell Farmhouse as Anna Sewell knew it.

Back in England Hack's old house at Graylingwell Farm, from which he had left for Australia, was occupied by another Quaker family, the Sewells, whose daughter Anna was later to become famous as the author of the children's classic "Black Beauty".

In Britain the nineteenth century was important for Friends in various ways: slavery was finally ended in 1838 after an Act in 1833; the first Friend took his seat in Parliament; George Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree established their famous businesses. Both were model employers: Cadbury built Bournville, a garden suburb, for his workers and the Rowntree family was responsible for the social research trust which bears their name. Many years later Seebohm Rowntree was to play an important part in the genesis of the first National Insurance Act, Churchill and Lloyd George both acknowledging his influence. In Chichester the two Lancastrian schools were a real achievement, albeit not by Friends alone.

In Britain the nineteenth century was important for Friends in various ways: slavery was finally ended in 1838 after an Act in 1833; the first Friend took his seat in Parliament; George Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree established their famous businesses. Both were model employers: Cadbury built Bournville, a garden suburb, for his workers and the Rowntree family was responsible for the social research trust which bears their name. Many years later Seebohm Rowntree was to play an important part in the genesis of the first National Insurance Act, Churchill and Lloyd George both acknowledging his influence. In Chichester the two Lancastrian schools were a real achievement, albeit not by Friends alone.

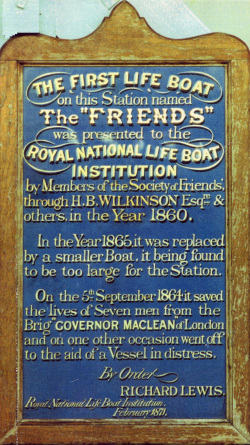

A local achievement by Friends nationally was the purchase of the first lifeboat to be stationed at Selsey. It arrived by train from London on 13th June 1861 and was received in Chichester with much ceremony. A procession was formed at the station gates and it was then towed up South Street with the boat’s crew seated aboard, led by the Chichester Police and the Band of the Sussex Rifles. At the Cross the Mayor climbed aboard and made a speech to (according to contemporary reports) a crowd of some three or four thousand. There was vociferous cheering and every window was filled as the boat was paraded up and down East Street before being towed down to the canal basin for a demonstration of its self-righting properties.

The boat finally arrived in Selsey the next day where a luncheon was held in its honour. Those present dined well and a somewhat verbose toast was proposed by one gentleman “To the Society of Friends without whose generosity etc etc”. The toast was warmly received and almost all present duly drank to the Quakers. After this came the call “Three cheers for the Society of Friends” and these were most heartily given – an unusual tribute to a somewhat ascetic sect which was at that period almost entirely teetotal.

The boat finally arrived in Selsey the next day where a luncheon was held in its honour. Those present dined well and a somewhat verbose toast was proposed by one gentleman “To the Society of Friends without whose generosity etc etc”. The toast was warmly received and almost all present duly drank to the Quakers. After this came the call “Three cheers for the Society of Friends” and these were most heartily given – an unusual tribute to a somewhat ascetic sect which was at that period almost entirely teetotal.

The boat was called 'The Friends', cost £180, and rescued seven men in 1864. After five years it was moved from Selsey as too large - lifeboats were rowed in those days - but it served a further nineteen years elsewhere, saving another fifty five lives.

An important development in mid-century (1861) was that Quaker dress and Quaker speech (thee/thou) were no longer insisted upon as essential for those undertaking service for the Society, and both quickly dropped out of fashion.

A service which became widespread shortly after was the Adult School Movement which, though most of the teaching was on Sunday, bore little relation to the Sunday Schools of today, being a literacy programme for men and women of all ages. It was through this movement that a young Anglo-German came to know Friends. He left Germany to avoid army service and, as a pacifist and a befriended traveller, his story was typical of Quakers who had always tended to pacifism and internationalism. The young man's name was Charles Hess and he had three daughters who were, many years later, to become valued members in Chichester.

Throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century the Chichester Meeting continued its decline, a number of the younger and more dynamic Friends had left for South Australia to join Barton Hack and by 1851 there were only an average of fourteen left worshipping on Sundays. By 1870 the total membership was thirteen, all of one family, the Smiths. Thomas Smith was the man who had come to Chichester in the 1820s to partner John Hack in the curriers. Like many of the newly enfranchised non-conformists of the day Thomas took a leading part in public life, he was a Liberal and rose to become Mayor in 1865. There weren’t many Quakers but the few who remained were people of influence.

William Smith announcing the Jubilee.

William Smith announcing the Jubilee.

William Smith, son of Thomas, was even more important in the civic life of Chichester – he too was elected Mayor, in 1886, and the West Sussex Gazette recorded that he affirmed rather than take the Oath “being one of those people called Quakers”. In 1887 he was Mayor again and took a prominent part in Queen Victoria’s Jubilee celebrations amongst other things planting the first memorial tree in Jubilee Park. His father died three years later at the age of ninety two and was the last person to be buried at Priory Road.

In all William served as Mayor six times, transferred the water works to the City Corporation, was the original promoter of the town drainage system, a Justice of the Peace, an Alderman of Chichester and Alderman of West Sussex County Council from its inception. He was made a Freeman of Chichester in 1905, one of only twenty three individuals in the twentieth century to be so honoured.

In all William served as Mayor six times, transferred the water works to the City Corporation, was the original promoter of the town drainage system, a Justice of the Peace, an Alderman of Chichester and Alderman of West Sussex County Council from its inception. He was made a Freeman of Chichester in 1905, one of only twenty three individuals in the twentieth century to be so honoured.

William continued to worship at Priory Road, but he was often alone in the simple, elegant, old room where so many had sat before. At that period meetings were held in the afternoon when the western sun would have slanted in on him through the sash windows which looked onto the graveyard and the trees of the Friars' Gate garden. In 1908, an elderly man and not in the best of health, he left the town to live with his family in Rustington, and the meeting house closed.

In a curious parallel development the Chichester Pennsylvania Meeting had so diminished that it also closed, in 1910, its members becoming part of the nearby Concord Meeting.

4: War and Pacifism 1908:1967

The Priory Road building remained closed for seventeen tumultuous years. The Great War started in 1914 and Friends became very unpopular because of their pacifism. Conscription was introduced and conscientious objectors imprisoned. In 1916 some were sent to France in order that they might, under the different regulations obtaining there, be shot as deserters, though the policy was reversed before any actual executions took place. Friends in Parliament were, with the Independent Labour members, instrumental in the introduction of a "conscience clause" to the Conscription Act. Many Quakers served in medical units and the young men of the Friends Ambulance Unit eventually gained considerable respect for their courage and care.

There was no Meeting in Chichester during these troubled times but one started again in 1925. William Hobson, a worker in one of the Quaker Adult Schools, had come to live in the neighbourhood and with his help Priory Road was reopened in the summer for two Sundays each month. In winter it opened on only one Sunday a month, there being fewer holiday makers to swell the gathering. A Monthly (administrative) Meeting was held at the Meeting House in 1928 but by February 1930 it was closed again, probably because of the cold and dark in winter. However meetings were being held, presumably in private houses, and a committee was appointed by the Monthly Meeting to discuss the situation with local Friends. One of the committee members was Ronald Littleboy, whose brother Wilfred was Clerk to the Yearly Meeting. As a young man Wilfred had re-established the Australian connection when he visited Adelaide in 1909, running some very memorable Young Friends’ Camps. Eleanor Littleboy, the niece of Ronald and Wilfred, was many years later to become Convener to the Elders in Chichester. The ‘Elders’ have a special responsibility for the spiritual life of the community.

The upshot of the 1930 discussions was that internal repairs were undertaken, at a cost of over sixteen pounds, and the following year a further seven pounds was spent on the installation of gas lighting, but despite this, in November 1931, meetings were discontinued "for the winter months". They were not to reopen for another ten years.

The problem at this time was that of a very thin spread of people over a very wide area, and the people in question were mainly reliant on public transport. Friends were not evangelical and did not build up a base of local support.

A guided walk party in the Burial Ground

A guided walk party in the Burial Ground

One matter achieved before the 1931 closure was that the Hornet burial ground finally became a Quaker freehold. The Council wished to take some of the land for road widening and initiated negotiations which led to the legal change - the four pence annual rent not having been paid since 1699. A strip of the newly acquired land was dedicated to the public for the new pavement and the rest was let to the Council, as a public garden.

The 1930s were a troubling decade. The autocratic militaristic regimes in Germany and Japan represented the antithesis of Quaker beliefs. Hitler came to power in 1933 and the first refugees began to arrive here. Dr Peter Aris, a judge who had spoken against the Nazis, arrived penniless and was befriended by Friends in Cambridge for whom he formed a deep respect. His daughter, Jan Tregear, became a member of the Chichester Meeting thirty years later.